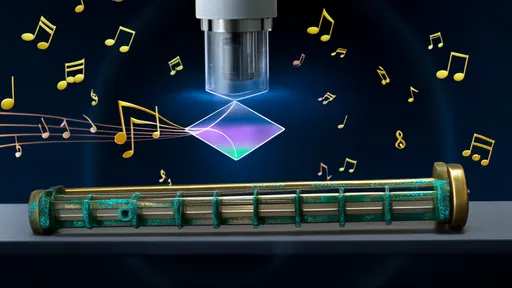

The art of Baroque basso continuo, or figured bass, represents one of the most fascinating and intricate aspects of historical performance practice. Unlike modern notational precision, Baroque musicians relied on a shorthand system of numbers and symbols to guide their improvisation. This practice was not merely a technical exercise but a deeply expressive language that allowed performers to breathe life into the music. The reconstruction of a theme using Baroque figured bass rules requires both scholarly insight and creative intuition, bridging the gap between historical accuracy and artistic interpretation.

At the heart of Baroque figured bass lies the concept of harmony as a fluid entity. The bass line, often played by a cello or viola da gamba, served as the foundation, while the harpsichord or organist interpreted the figures—numbers and accidentals—to construct chords in real time. This improvisational freedom was not anarchic; it followed strict conventions that varied across regions and composers. For instance, a 6 above a bass note typically implied a first-inversion chord, while a 7 indicated a dominant seventh. Yet, the performer’s choices in voice-leading, ornamentation, and rhythmic articulation could transform a simple progression into a richly layered tapestry.

Reconstructing a theme using these rules demands an understanding of contrapuntal logic. Baroque composers like J.S. Bach or Georg Philipp Telemann wrote with an inherent sense of vertical and horizontal coherence. The figures provided a skeleton, but the flesh came from the performer’s ability to weave inner voices with elegance and purpose. Dissonances were not avoided but savored, resolved with deliberate grace. For example, a suspended fourth resolving to a third over a descending bass line could evoke profound pathos, a technique frequently employed in operatic recitatives.

The improvisational aspect of figured bass also highlights the collaborative nature of Baroque music. Unlike the rigid hierarchies of later classical ensembles, continuo players engaged in a dynamic dialogue with soloists. A skilled harpsichordist might mirror a violinist’s trills or anticipate a singer’s cadential flourishes, creating a responsive and ever-evolving performance. This interplay was documented in treatises by Johann David Heinichen and C.P.E. Bach, who emphasized the importance of adaptability and listening.

Modern attempts to revive this practice often encounter challenges. One is the temptation to over-embellish, drowning the original material in excessive ornamentation. Another is the rigidity of academic reconstruction, which can stifle spontaneity. The balance lies in respecting historical frameworks while embracing the improvisatory spirit that defined the era. Workshops and masterclasses led by specialists like Jordi Savall or William Christie have demonstrated how alive and relevant this centuries-old practice remains today.

Ultimately, the reconstruction of a Baroque theme through figured bass is more than an academic exercise—it is an act of rediscovery. It invites us to hear familiar works with fresh ears, to appreciate the interplay between notation and imagination, and to reconnect with a time when performance was inseparable from creation. As we delve deeper into this art, we uncover not only the techniques of the past but also the boundless creativity they inspire in the present.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025